Community

For the Love of Saltmarsh

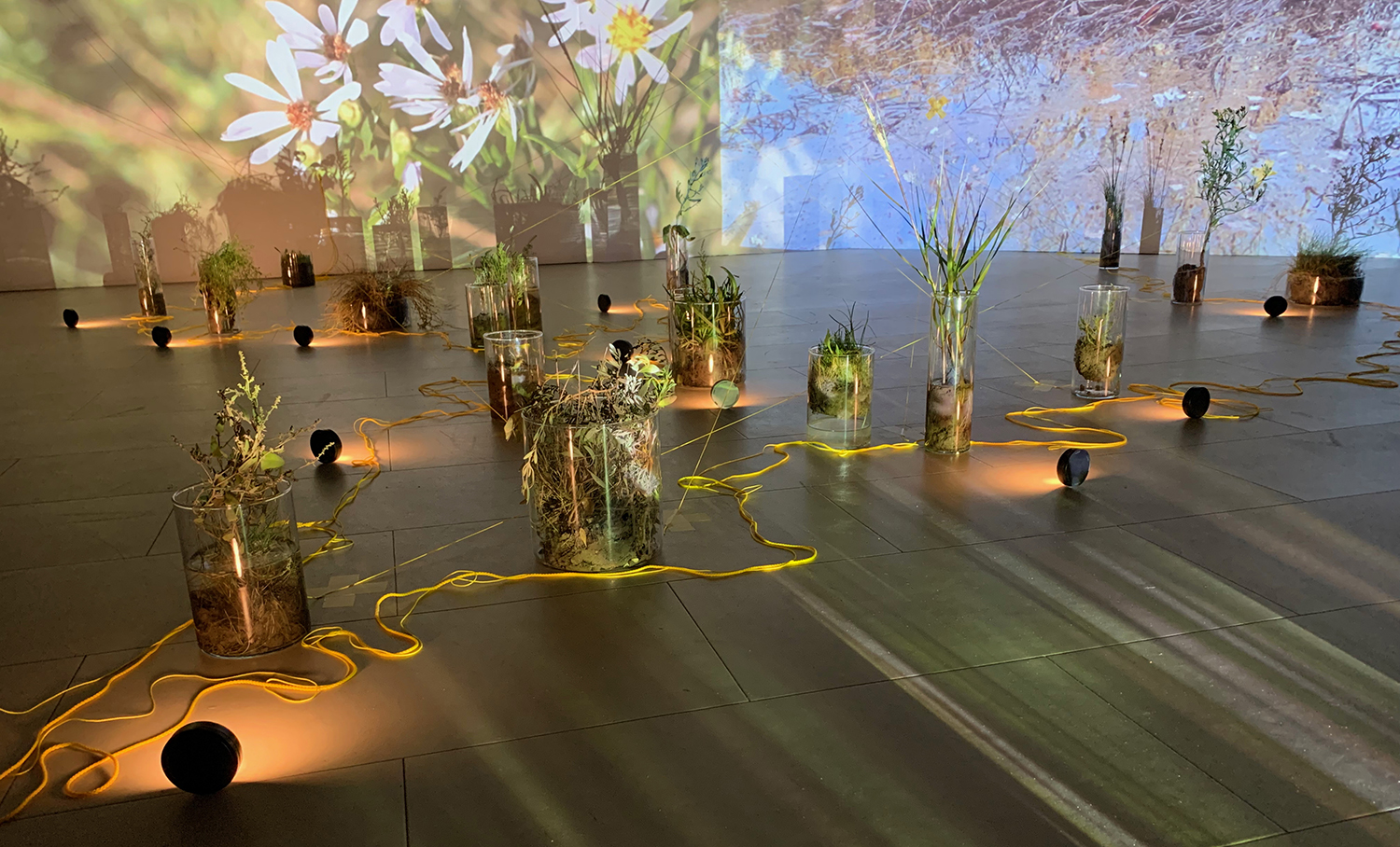

The UK Saltmarsh Forum's theme this year was environmental connectivity. BLC brought an arts-led track to the event with a boots-in-the-mud story of collaboration and an installation that spoke to how we perceive, feel and understand saltmarshes.

“It was as though Saltmarsh was a collaborator.”

This was artist Beth Heaney’s sense of what it felt like to be part of The Saltmarsh Project, the 3-year, 13-partner, 6-artist ecosystem restoration programme to restore 4 hectares of saltmarsh on the upper shores of the Dart Estuary in South Devon. As the lead for community participation, Bioregional Learning Centre (BLC) co-managed the Project, intentionally centering the arts as part of a spirited and effective form of collaboration.

Beth was speaking as part of the UK Saltmarsh Forum, 2nd-3rd September 2025, on campus at Swansea University, which included an arts-led participatory track produced by BLC. The film screenings and Q&A session (Part I) and art installation (Part II) echoed the public events previously delivered as part of The Saltmarsh Project. The intention translated perfectly - shifting focus beyond human goods and benefits toward a more relational understanding of this vital but fragile habitat. But here in South Wales, we were in a different bioregion with its own saltmarshes, alongside geographers, scientists, researchers and PhD students. That called for a different kind of collaboration and artistic response. For the Forum itself, we would only have 3 hours with attendees who represented saltmarshes from all over the UK. Despite the brevity of the interaction, we wondered… could this be a first step in creatively connecting saltmarshes (and their communities of interest) worldwide?

For the Love of Saltmarsh Part I

The first day of the Forum had been packed with talks centered on environmental connectivity. That evening, over 100 academics and locals were seated in the auditorium, having just watched a series of film shorts that included theatre director Sophie Hunter’s Salt of the Earth and the premiere of BLC’s 11-minute film, For the Love of Saltmarsh, that poses the question, 'is this what local, creative and respectful ecosystem restoration looks like?'

Our film portrays the Dart's constellation of saltmarshes and encapsulates everything you might want to know–the habitat, why it’s ‘useful’, how it makes us feel, the people involved, and how understanding leads to valuing and conserving. Its title comes directly from the words of Forum Chair, Angus Garbutt, Senior Ecologist with the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, in describing the relational nature of the Forum’s gatherings, growing organically in number over the years; “for the love of saltmarsh, that's why we do it”. That was exactly how we felt, we had fallen in love with saltmarsh, too.

For Q&A, Angus was joined on stage by Dr Cai Ladd, Senior Lecturer in Geography, and Saltmarsh Artist Collective collaborators, Jane Brady, Emilio Mula and Beth Heaney. The Collective formed organically out of The Saltmarsh Project, which, from its outset, paired scientists with artists. Comments and questions flowed and seemed to lean towards a curiosity about our creative process. Boatbuilder and marine biologist from Bangor University, Martin Skov, acknowledged the importance of emotional response (as sensing and the awareness of that sensing) in understanding a habitat like saltmarsh.

Exchanges with the audience gave rise to stories from the local saltmarshes. Gower Salt Marsh Lamb is considered tasty because it is the product of a lifetime of grazing on samphire, sorrel, sea lavender and thrift, and evokes a long tradition of human connection to the saltmarsh. ‘Granny’s custard’, sticky estuary mud, formed at the same time as the original oak and hazel forest and peat bogs in Swansea Bay, which grew when sea levels were lower, about 5,000 years ago. We are keen to hear more saltmarsh stories from all over the UK because they have a stablising effect, and bring us closer to appreciating a place... although perhaps not as much as actually tasting it! Coriander-flavoured Marsh Arrowgrass, for example.

For the Love of Saltmarsh Part II

The art installation explores a way to sense the essential nature of saltmarsh, set alongside the ways in which we describe, measure and value it. It proposes: 'We can use words to describe it, maps to locate it, quadrats to define it, percentages of Blue Carbon to measure it, images to represent it, but are we losing sight of something?’ More than edges or lines on a map, saltmarshes are unique ecosystems belonging to land, river and sea, part of a fluidscape. In their quiet resilience they teach us how to live with change.'

“As an artist, working for and with the saltmarsh meant that I wasn’t at the centre of things. The Dart’s saltmarshes became a collaborator, a muse… having its own character particular to South Devon, but also connected to their saltmarsh relatives all over the world” - Beth Heaney

‘Seeing’ a whole ecosystem at once (let alone a whole bioregion) is impossible, of course, given its complex and emergent state, but we can notice and record moments or snapshots - of habitats, exchange, activity, change, history or lived experience within human and non-human communities. What becomes apparent then, is ‘seeing’ in terms of dynamic, intricate webs of relationships. Moreover, occupying our own senses while doing so is a way to broaden awareness, and perhaps to realise what has been muted in ourselves or commodified in our surroundings. To quote philosopher Barry C. Smith in conversation with artist Olafur Eliasson1, "I think our senses - and the crosstalk between the senses - can help people unblock experiences, make better judgements and really know their own preferences. By knowing better why they like something, they'll be able to engage with it more." Eliasson adds, "I think it is crucial for people to see themselves as being participants in the world - producers rather than simply passive consumers."

“Sensing is a way to begin a conversation, to see that we ARE nature, a practice that amplifies a feeling, activating care and love from that understanding.” - Emilio Mula

Bioregional Context

Thinking and acting bioregionally requires us first to think in wholes: whole rivers, whole catchments, whole landscapes, whole systems. And then to respond in a robust, systemic way given actual and expected climatic stimuli and their effects, where geo systems (ocean currents, land and sea temperatures, atmospheric currents) are becoming increasingly unstable, colliding with human systems and ecosystems.

The UK's 50,000 hectares of saltmarsh lock away thousands of tonnes of carbon dioxide every year. Saltmarsh restoration, as an action for climate adaptation, is a doable adjustment, a change in processes, practices and structures, 'with nature', to moderate damage associated with climate change, such as disruptions to food webs, erosion and flooding. According to the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, unlike rainforests, which take centuries to bounce back from disturbance, saltmarshes are fast workers, springing back to life and creating vibrant habitats in just a few years. Respectful ecosystem restoration is a no-brainer, alongside the work needed for these times–putting in place the networks, knowledge sharing, finance, learning pathways, partnerships, decision-making, expertise and region-wide projects that can underpin a regenerative response and our evolution into an ecological future. As animator, meaning-maker and activator, the arts have a vital role in every aspect of this work.

We have discovered that getting to know the Dart’s saltmarshes strikes a chord–within us as individuals, as a team, and within many people. Nestled into small, hidden, or inaccessible parts of this Ria-type estuary, saltmarshes live at the threshold of the bioregion, filtering all that comes in and out. Saltmarsh plants are opportunistic, spreading seeds and migrating into new areas in response to their changing environment.

What else can the saltmarshes teach us, this boggy stuff of mystery?

"Social change doesn't happen through a single person (in general), and it certainly doesn't happen through a single art project. It happens through the collective activity of many, many people working in many ways to push the ball up the hill in the same direction." - Suzanne Lacy, social practice artist, 20182

1 From the book/exhibition at the Tate: Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life, edited by Mark Godfrey

2 From the book/exhibition: Everyone Is an Artist: Cosmopolitical Exercises with Joseph Beuys, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf/Hatje Cantz